Participatory Urbanism

Urban Atmospheres' Participatory Urbanism presents an important new shift in mobile device usage - from communication tool to “networked mobile personal measurement instrument”. We explore how these new “instruments” enable entirely new participatory urban lifestyles and create novel mobile device usage models.

In the spirit of Urban Computing, Participatory Urbanism is the open authoring, sharing, and remixing of new or existing urban technologies marked by, requiring, or involving participation, especially affording the opportunity for individual citizen participation, sharing, and voice. Participatory Urbanism builds upon a large body of related projects where citizens act as agents of change. There is a long history of such movements from grassroot neighborhood watch campaigns to political revolutions. It is not a disconnected personal phone application, a domestic networked appliance, a mobile route planning application, an office scheduling tool, or a social networking service. Participatory Urbanism promotes new styles and methods for individual citizens to become proactive in their involvement with their city, neighborhood, and urban self reflexivity. Examples of Participatory Urbanism include but are not limited to: providing mobile device centered hardware toolkits for non-experts to become authors of new everyday urban objects, generating individual and collective needs based dialogue tools around the desired usage of urban green spaces, or empowering citizens to collect and share air quality data measured with sensor enabled mobile devices.

Our mobile devices are more than just personal communication tools . They are globally networked, speak the lingua franca of the city (SMS, Bluetooth, MMS), and are becoming the dominant urban processor. We need to shatter our understanding of them as phones and celebrate them in their new role as measurement instruments. Our desire is to provide our mobile devices with new “super-senses” and abilities by enabling a wide range of physical sensors to be easily attached and used by anyone, especially non-experts.

We argue there are two indisputable facts about our future mobile devices: (1) that they will be equipped with more sensing and processing capabilities and (2) that they will also be driven by an architecture of participation and democracy that encourages users to add value to their tools and applications as they use them.

Personal, Mobile Air Quality Measurments

an example of Participatory Urbanism

Millions of us carry a mobile device such as a mobile phone with us everyday. For all of its computational power and sophistication it provides us very little insight into the actual conditions of the terrain we traverse with it. In fact the only real-time environmental data it renders is a narrow slice of the electromagnetic spectrum with a tiny readout of cell tower signal strength using a series of bars

The World Health Organization estimates that 2 million deaths each year can be attributed to air pollution - that’s more deaths than those resulting from automobile accidents. Presently, citizens must defer to a small handful of civic government installed environmental monitoring stations that use extrapolation to derive a single air quality measurement for an entire metropolitan region. This sparse sensing strategy does little to capture the dynamic variability arising from daily automobile traffic patterns, human activity, and smaller industries. Are we to believe that the park, subway exit, underground parking lot, building atrium, bus stop, and roadway median are all equivalent environmental places?

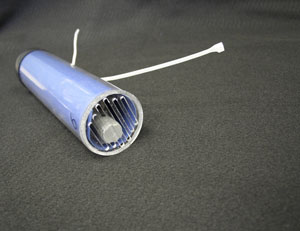

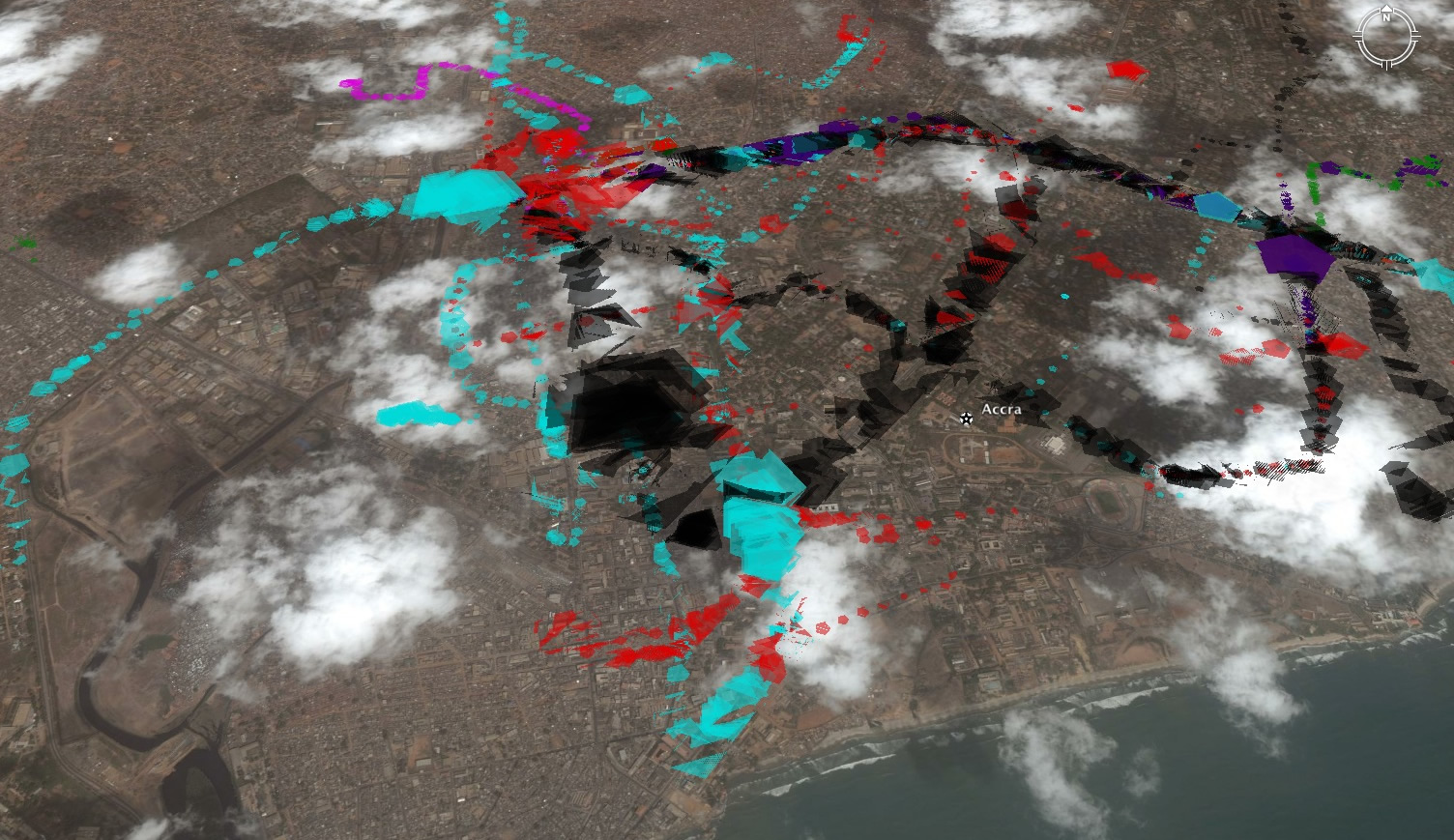

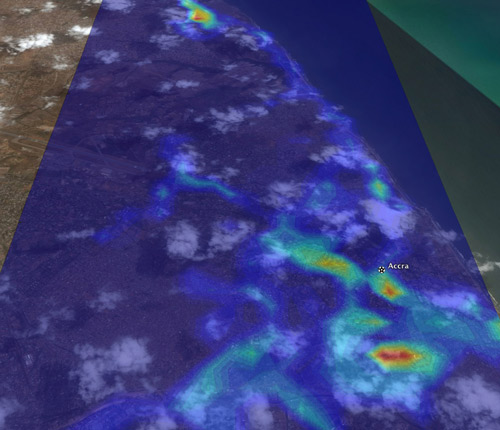

We collected two weeks of environmental data from taxicabs moving across the city of Accra, Ghana that illustrates the wide air quality fluctuations. The taxi mounted tube air sampler with carbon monoxide, sulfur dioxide, and nitrogen dioxide sensors exposed and packaged are shown below. Also, several individuals collected data throughout the day using a body worn setup containing similar air quality sensors and GPS unit also shown below.

Carbon Monoxide readings across Accra, Ghana. Colors represent individual taxicabs, patch size indicate the intensity reading of carbon monoxide during a single day across the capital city of Ghana. Note the variation across the city and within small neighborhoods.

A different heat-map visulaization of Carbon Monoxide readings across Accra, Ghana. Colors represent individual the intensity reading of carbon monoxide during a single day across the capital city of Ghana. Note the variation across the city, within small neighborhoods, and on the approach to the international airport

What happens when individual mobile devices are augmented with novel sensing technologies such as noise pollution, air quality, UV levels, water quality, etc? We claim that it will shatter our understanding of these devices as simply communication tools (a.k.a. phones) and celebrates them in their new role as measurement instruments. We envision a wide range of novel physical sensors attached to mobile devices, empowering everyday non-experts with new “super-senses” and abilities. It radically alters the current models of civic government as sole data gatherer and decision maker by empowering everyday citizens to collectively participate in super-sampling their life, city, and environment.

Integrating simple air quality sensors into networked mobile phones promotes everyday citizens to uncover, visualize, and collectively share real-time air quality measurements from their own everyday urban lifestyles. This rich people-driven sensor data leverages community power imbalances, and can increase agency and decision maker understanding of a community's claims, thereby potentially increasing public trust. This detailed local knowledge informs environmental health research and environmental policy making – persuading both individuals and civic government towards positive improvements in air quality and environmental change.

This system shows individuals a pattern of their own behavior that may not be easy to discern without such a tool and application. The air quality that an individual encounters varies by time of day, route and mode of travel, and time of year. Individuals are also able to compare the levels of air pollution they are exposed to daily with that of their friends, family, or other citizens in not only their own metropolis but across global cities. We hope to promote continued use by bringing these environmental phenomena and patterns to the individual’s attention.

Using the N-SMARTS hardware from UC Berkeley we are designing hardware and software mobile systems to enable Participatory Urbanism.

Stay tuned as we invite you to measure and share your own personal environmental data using these new mobile devices and tools over the coming months.

Let's all participate!

Also check out Ergo a text messaging system for receiving air quality reports designed by Urban Atmospheres

Envisioned Scenarios

Mary suffers extreme problems with her asthma when she is in her yard gardening. But the air and pollen counts for her city are consistently reported as below normal. However, Mary’s particulate matter sensor on her mobile phone reports dangerous levels of exposure from wood burning pollutants. Checking a selection of sensor data from people who also take measurements on her block, perhaps her neighbors, Mary is able to see that the problem is concentrated around a single cul-de-sac near her. Mary soon notices that several homes in that area are continuously using their fireplaces and generating excessive airborne pollutants, which are forbidden by local ordinance. Mary forwards the measurement collection to her local air quality measurement district where action is taken to enforce the clean air policy

A strong odor suddenly overwhelmed residents of New York City. Emergency crews were unable to pinpoint any gas leaks or other causes. The uncertainty caused anxiety and fear in citizens even after the odor dissipated the next day. After searching 140 industrial facilities officials declare that hey are giving up hope of finding the source of the mysterious odor.(This is what really happened on 8 January 2007 in New York. What follows is where Participatory Urbanism makes a difference. ) However, the odor left trace nitrogen dioxide measurements as logged by millions of New Yorkers mobile phones and a simple mashup of the data set on google maps identifies the culprit – a dangerous incinerator that is not suppose to be in use. City officials shutdown the plant immediately.

Tyler lives in Lagos, Nigeria where his family often cooks indoor using charcoal. Tyler’s son is suffers nearly every two weeks from respiratory problems. However, the government just received another award for outstanding regional air quality. Tyler checks his mobile phone’s sulfur dioxide sensor and realizes that several hazardous level measurements were taken about two weeks ago. Tyler compares his measurements to others shared online and realizes the problem occurs during indoor cooking using freshly cut wood. Tyler alerts others with similar measurements to the problem and successfully petitions the government to provide new cleaner sources of cooking fuel based on his and others reported measurements.

Eric Paulos (Intel Research Berkeley)

Ian Smith (Intel Research Seattle)

RJ Honicky (UC Berkeley)

Related Work

A collection of several inspirational projects:

Urban Sensing (CENS / UCLA)

SensorPlanet (Nokia)

AIR (Preemptive Media)

SenseWeb (Microsoft)

The Urban Pollution Monitoring Project (Equator UK)